News | June 5, 2018

Bill Patzert Retires

Article By Mark Whalen JPL Universe February 2018 Volume 48, Number 2

Patzert came to California after earning a master’s and doctorate in oceanography from the University of Hawaii. He was there at the start of serious studies of El Niño, and helped pitch a new program centered on doing oceanography from space to NASA -- which turned into the TOPEX/Poseidon mission that measured the surface height of the ocean, providing valuable data about our changing planet. The climate data record begun by TOPEX/ Poseidon now extends more than a quarter century.

Universe caught up with Patzert for a chat about his love for the ocean and his best memories of JPL.

Q: What was your inspiration to study Earth science?

It started with my father. He was a sea captain and operated a commercial fishing boat out of Long Island, N.Y. in the late 1940s. From a young age, I would often go out to sea with him. My dad loved the water, and had a deep respect for nature.

When I was growing up, he would take me outside and we would shoot the stars with a sextant, trying to locate our backyard, which we did -- hundreds of times.

I remember the first books he bought for me were Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and The Sea Around Us. So, from an early age, I was steered toward respect for the environment and oceanography.

In college, at Purdue University in Indiana, I majored in math and physics, a double major, and a double minor, in geology and American literature. Purdue was far from an ocean.

So when it came time for graduate school, I was ready for a change -- what I really wanted to do was go to Hawaii and become a big-wave surfer.

Q: Well, you did that, didn’t you?

I did. I spent seven years in Hawaii, surfing the waves all around Oahu. But in spite of my wayward ways and as fate would have it, my mentor there was one of the early researchers in large-scale climate research, as well as El Niño.

After graduate school, I headed for California. My first job was at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. The beach in La Jolla sealed the deal. I could continue my surfing as well as my academic career. At Scripps, I was a sea-going oceanographer and led expeditions in most of the oceans. My research was focused on large-scale climate connections, especially on El Niño.

I was happy at Scripps, but in the early 1980s oceanography was about to change. These were the early days of NASA Earth science and I had an opportunity to join a team of visionary folks who were dreaming of and organizing an oceanography from space program. I joined this team at NASA Headquarters and helped organize, design and sell a big program, which turned out to be the U.S./ French TOPEX/Poseidon mission that was managed here at JPL.

Let’s take a look back over the length of my career. In the mid-1980s, an interesting thing happened – in society as well as in science. It was the birth of desktop computing.

I had to type my doctoral thesis on an IBM Selectric typewriter. We had no word processing or desktop computing capability. At the same time, NASA was preparing to revolutionize meteorology and oceanography.

In the late ’70s and early ’80s, NASA and NOAA had already launched the first weather satellites; oceanography arrived in space when TOPEX/Poseidon was launched in 1992. By that time, we had desktop computing. But the interesting thing that happened in the 1990s is what complemented desktop computing -- the internet.

So, from the beginning of my career at JPL, we went from electric typewriters, to desktop computing, to the internet.

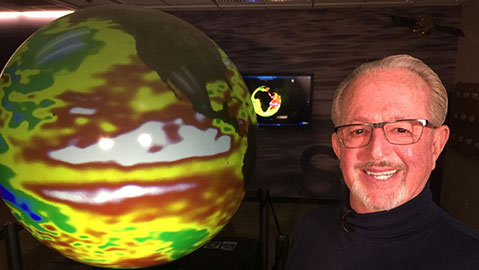

We launched TOPEX/Poseidon, and from the start of the mission it was wildly successful. After 25 years of monitoring the global oceans, it has revolutionized oceanography and climate science. One of the key climate measurements is sea level. Ninety-five percent of the heat from global warming is captured in the ocean. So the unequivocal proof of global warming is sea-level rise. We measured it, and it’s now an unequivocal scientific fact.

So all these things came together: the tech revolution, internet, satellites that could monitor essentially what was historically an inaccessible global ocean. Then the 1997-98 El Niño hit, just as all these things were peaking. We were riding a tsunami of many factors.

Within a couple of years of that ’97-’98 El Niño, more than a billion people around the planet had seen our JPL TOPEX/ Poseidon El Niño images, and I became a fixture on reporters’ Rolodexes.

Now, part of this was luck. It’s not just me -- JPL scientists in general have benefited from where we are located, how close we are to the media, and Los Angeles being the second-largest media outlet in the United States. All the main media outlets -- radio, TV, newspapers, internet -- all are within an hour of JPL.

Very rapidly, I was doing interviews in studio, on Lab, at home -- Monday through Sunday. And people just loved how JPL visualized El Niño. There was something that tweaked the media’s cerebral cortex about El Niño.

Let’s not forget that we also had a keen focus on another significant climate pattern. Following the El Niño of 1997-98, the equatorial Pacific shifted to a cooler pattern, La Niña, that often has the flip impacts of El Niño. So, my research switched to understanding the relationship between the warm El Niño to his cooler sibling, La Niña.

The satellite data revealed even larger and longer-lasting patterns that influence the frequency and intensity of these two phenomenon. One of those patterns is the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, a slow-moving variation of temperatures between the western and eastern sections of the Pacific. In 1998, the western portion was becoming warmer than the eastern portion, leading me to conclude that in the long term, an El Niño–repellant pattern was forming that would favor drought in Southern California for many years.

Now we have 25+ years of continuous data, with TOPEX/Poseidon and Jasons 1 through 3, and the next satellite in the series, Sentinel 6, in the queue. And remarkable things happened, not just El Niño. The measurements were so well done, so precise, that we actually measured global sea-level rise -- which now is about 3 millimeters per year. So over the last two and a half decades, the rise in sea level has been almost three and a half inches.

Q: Can the average person make sense of what that means?

In a scientific sense, it’s the unequivocal proof of global warming. Sea-level-rise projections are now at an inch per decade. Global sea-level rise is projected over the next 50 to 100 years to be anywhere between 2 and 6 feet -- which will rewrite coastlines across the planet. It is the real deal and is now part of public policy.

Q: Have there been cases where public policy was improved due to the TOPEX/Poseidon and Jason data?

One thing for sure is that El Niño forecasting is taken much more seriously than it was 25 years ago. It’s better understood, so the forecasts have dramatically improved. Of course, with sea-level rise happening all across the planet, our data are now factored into not just present public policy, but public-policy planning. People are actually building adaptations to deal with sea-level rise. It will become a multi-billion-dollar issue. Our JPL measurements -- which show that sea-level rise is climate change -- are embraced by policy makers across our planet.

Q: What has been your approach in dealing with the news media?

I’m a generalist, because I can talk about the societal implications, or how different missions overlap, how it all fits together in the big picture. I learned a long time ago that as a communicator, if you just do one thing and it’s climate related or technically innovative, you’re going to have a half-dozen interviews a year if you’re lucky. So early on, I thought, what do the media talk about every day? What is the public always interested in -- every day?

It’s the weather. I’ve worked with all the local TV news and weather-forecasting journalists for two and a half decades. I haven’t given them many bum steers. Well, maybe a few. Nobody’s perfect. But I can weave an interesting story. I use a lot of alliteration and a little humor to tell stories that are relatable.

It’s good to be a scientist in an ivory tower, but the long-term goal of any scientist is to understand -- in this case, how the climate works -- and to test your theories by making credible forecasts and predictions.

I keep a running tally on the rainfall. From mid-February 2017 to early-January 2018, we had less than an inch of rain in downtown Los Angeles.

I know that right off the top of my head. In the rain year starting Oct. 1, downtown L.A., and most of Southern California, were at 5% of normal. Until the storms that came the second week of January, it’s the longest and driest Santa Ana period I’ve seen in Southern California during my career.

All the stationary high-pressure systems in December are related to the jet stream patterns. The jet stream goes far to the north over the west, then swoops down into the Midwest and northeast. The flip side of a heat wave in L.A. is frigid weather in Washington, D.C. and New York.

Q: It seems you are having a great time explaining nature to people. True?

Yes, of course, I love to do it. But there are certain rules on communications.

You’re much more credible if you’re smiling and happy, and you’re talking slowly and loudly. Articulate and enunciate. That’s part of my nature and, mostly, many years of practice.

How many different Hawaiian shirts have you seen me wear? It cheers people up.

Q: What are the keys to successful interviews?

It’s preparation, preparation, preparation -- that makes the interview seem seamless. The one thing you cannot do if you’re on TV is sit there and look at your notes; you’ve got to look right at the camera or at the reporter. If you lose eye contact with the reporter, you’ve lost it.

I try to find simple words. For example, instead of making a complicated comparison between years of data, sometimes I do one of my famous quotes, such as: “It’s so hot in Riverside, the cows are giving powdered milk.”

There’s not a lot of time to get your point across. The average interview on the evening news lasts two minutes.

Here’s a tip: Before the interview, ask them what the segment is about. They’re only going to make one or two points. Just tell me what you want, and I can give it to you in a clean, concise way.

Why is all this important? At JPL, we’re doing cutting edge, important science. We do things at JPL that nobody else in the world does, and a critical part of this is to communicate it -- not only with our colleagues, but also the media and the general public. And the conduit for that communication is the media. You might have the story, but they’re the storytellers.

Most of these people are pros, and they all want to get it right. I always figure give them the maximum amount of cooperation, don’t confuse them, treat them with the highest level of respect, and they will tell your story well -- to the world.

You’re in a partnership with the press. They need you for news, and we need them to tell our great stories.

Q: Didn’t you make the news once during an El Niño, not for your expertise, but for the storm’s effect on your house?

Yes, during a heavy rainstorm in 1997 I actually had a leak in the roof that went right into my bedroom. Dan Rather of CBS News and I talked about it on national TV.

At that time, every Friday night during the fall and winter of 1997, Dan and I did the “El Niño Watch.” At the end of the show, we would have a mano-a-mano interview – I was here and Dan was in New York. That program went on for three or four months.

As I think back, I did it for a long time, and never really screwed up that bad. I rationalize that it was good for NASA, good for JPL. And it was good for science.

Yes. My one regret is that I never learned to speak Spanish.

In addition to all the local TV stations and American networks, Telemundo, a Spanish-speaking network, actually has a bigger viewing audience than some of the major American networks. They are seen all over the United States, and throughout Latin America.

Q: Have you had any help from JPL Spanish speakers?

Yes, I’ve had great help from two colleagues: Veronica Nieves, from Spain; and Erika Podest, from Panama. Erika and I just did a five-part special for Telemundo on climate change and ecology. For her part, they didn’t have to translate. For my part, they had to.

Q: What has changed for the better at JPL since you started here?

One of the things that has changed the most about JPL during my career is that it’s more diverse.

JPL looks a lot more like California than when I was hired. JPL is getting smarter and better. It looks a lot like the future of America. And it’s a good thing.

Q: Now that you have retired from JPL, will you also retire from public life? Or are there some future lectures still to come?

I already have some lectures scheduled for after my official retirement day [Jan. 18]. I might be 76, almost 77, but I want to continue to make a difference.

I’m planning to volunteer for some humanitarian and environmental work.

Q: Final thoughts?

I’m pretty upbeat about JPL. To be sure, it’s been an exciting career. It’s been a privilege to work with so many talented women and men. Being a part of the great TOPEX/Poseidon team was fantastic. I’ve given more than 10,000 interviews. Wow, I’m one lucky surfer.

I’ve been fortunate to receive a lot of support from JPL, from the directors, from the Media Relations Office. Whatever I accomplished in my career was because of the great teams of scientists, engineers and communicators that I’ve worked with. I turned into a team player, in spite of my natural tendencies.

It’s a natural time to pass the baton on to the younger generation, who have different skills and will do an even better job. Because the media of today is not the media of 1997.

Q: Will someone at JPL step right into what you’ve been doing?

No. I don’t think anybody will ever do it like I did it again. On the other hand, I think some of the younger people will be better trained and less timid about developing relationships with the media. Because if they don’t, it would be a shame.

You can’t leave and tell everyone what to do. Let the young people figure it out. In some ways, we’re just at the beginnings of the potential of the internet. Young people are more technically skilled and agile; they’ll do it differently, improve on what we have done.

I was 42 years old when I got my first desktop computer. Now these young people are using iPhones in kindergarten. So, the next generation of science communicators will look different than me, they will do it differently than I did. But I’m optimistic, not only about what JPL will do over the next few decades, but how we will communicate it.