News | March 16, 2017

Could Leftover Heat from Last El Niño Fuel a New One?

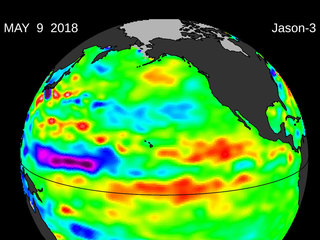

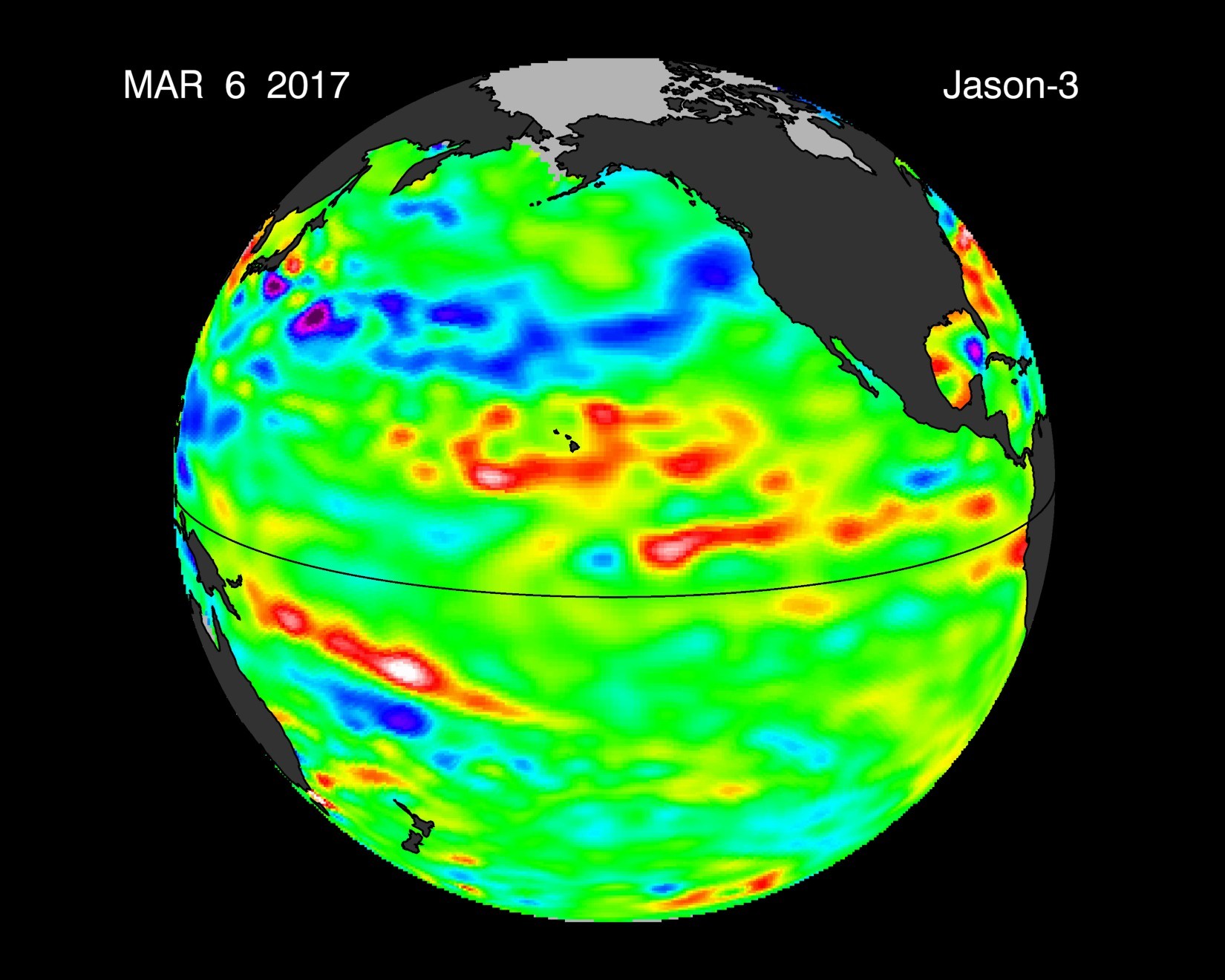

Some climate models are suggesting that El Niño may return later this year, but for now, the Pacific Ocean lingers in a neutral "La Nada" state, according to climatologist Bill Patzert of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California. The latest map of sea level height data from the U.S./European Jason-3 satellite mission shows most of the ocean at neutral heights (green), except for a bulge of high sea level (red) centered along 20 degrees north latitude in the central and eastern Northern Hemisphere tropics, around Hawaii. This high sea level is caused by warm water.

Whether or not El Niño returns will be determined by a number of factors, one of which is the larger stage on which El Niño and La Niña play, the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). The PDO is a large-scale, long-term pattern of ocean temperature and other changes in the Pacific Ocean. It alternates between two phases, warm (called positive) and cool (negative), at irregular intervals of 5 to 20 years.

The phases of the PDO are known to affect the size and frequency of the shorter-term El Niño and La Niña events. In its positive phase, the PDO encourages and intensifies El Niños. In its negative phase, it does the same for La Niñas. The last PDO phase shift was in 2014, when it turned strongly positive and has remained that way for 37 months.

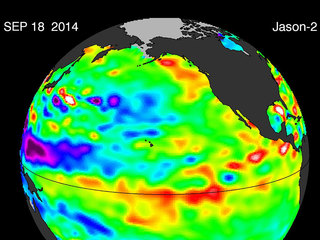

Patzert says a look back over the three years since the PDO's 2014 phase shift provides some clues about why the 2015-16 El Niño was so large and long-lasting, and why the 2016 La Niña was so small.

In 2014, Patzert says, the trade winds (the prevailing winds that blow from east to west over Earth's tropical oceans) in the Pacific Ocean weakened, and a modest El Niño waxed and waned throughout the year. It never fully developed, but it left the equatorial Pacific warmer than normal. In 2015, the trade winds dramatically weakened, triggering a big El Niño with major worldwide impacts. With a large pool of warm equatorial water to draw on, it formed early and strengthened for more than a year, reaching full strength in late January 2016 -- unusually late for an El Niño event.

Besides being long-lived, the 2015-16 El Niño was also unusually large in area, with high sea levels and warm water spreading as far north as Hawaii. As the main region of the El Niño waned, this warm bulge north of the equator remained.

During the summer of 2016, a La Niña was thought to be imminent, but it never truly took hold. By November 2016, the equatorial Pacific Ocean was in the neutral condition it remains in now. The high sea level visible as a red area around Hawaii in the new image is caused by warmth left over from the last El Niño.

Patzert postulates that the leftover warm-water bulge was responsible for the lackluster La Niña. "Did the warm bulge suppress the trade winds in the eastern and central Pacific, muting the conditions required for a full-blown La Niña to form?" he asks. "As all El Niño researchers know, no two El Niño or La Niña episodes are exactly the same."

Patzert and other researchers have additional questions about the PDO's influence. What role did the 2014 PDO phase shift play in the events of the last three years? Does the ongoing ocean warmth signal that the current positive PDO phase will be long lasting -- perhaps decadal -- or will it be a shorter-term blip? NASA scientists will continue to monitor the Pacific to see what's in store next for the world's climate.

Either way, Patzert notes, the PDO will be a factor in future climate patterns. "A warmer or cooler Pacific Ocean will certainly play a big role in future El Niño and La Niña events. That's important, because these events modulate drought and deluge patterns in the American West, as well as the rate of climbing global temperatures," he says.

For a time sequence of the evolution of the 2014 El Nino, visit:

http://sealevel.jpl.nasa.gov/science/elninopdo/latestdata/archive/

To learn more on NASA's satellite altimetry programs, visit:

Alan Buis 818-354-0474

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California

Alan.Buis@jpl.nasa.gov

2017-069